Where we choose to create says a lot about how we create

If I told you to picture in your mind’s eye a painter at work, I’m sure you creative readers could conjure a vast array of different concepts. Some may imagine a Pollock-type hard at work in the organized chaos of a studio. Others may even picture an elusive Banksy stealing glances over their shoulders for any Bristol police. Chances are, however, that a good number you pictured an artist set up with a folding easel, paint tubes, and weather-appropriate clothes painting outdoors. This archetypal image of the painter is a vision of painting En Plein Air.

In a short view of historical context, landscape painting has been around as long as anyone alive can remember. However, in the grand scheme of western art history it’s practically still a novelty to paint nature for nature’s sake. The rise of plein air painting and the happenstantial popularity of the impressionists was by its very nature an act of rebellion against a system that restricted what art was and what it most certainly was not.

Western painting had, for centuries, been contained to the studios and workshops of master painters. Instruction had more in common with the trades and subject matter was tightly controlled through the whims of patrons. The French Academy instructed students in the same neoclassical tenets that had guided visual artists since the renaissance. Compelling art was being made, but a cadre of creatives clearly couldn’t help but feel there was something left yet unexplored.

Advancements in available materials finally made it possible for artists to create finished paintings outdoors. Field easels and especially tubed paints allowed artists to freely explore, interpret, and record the natural world. Treating the landscape as a subject worthy of the artist was a radically new concept that represented the shift away from the primacy of human accomplishment towards recognizing the elegance of nature. Despite the upset to traditional forms of art education, creation, and patronage it ended up transforming public perception of art and artists. No longer was the artist only a trademaster at work in a studio surrounded by apprentices. Now you also got to see them waving a brush around outside and trespassing on your farms and forests.

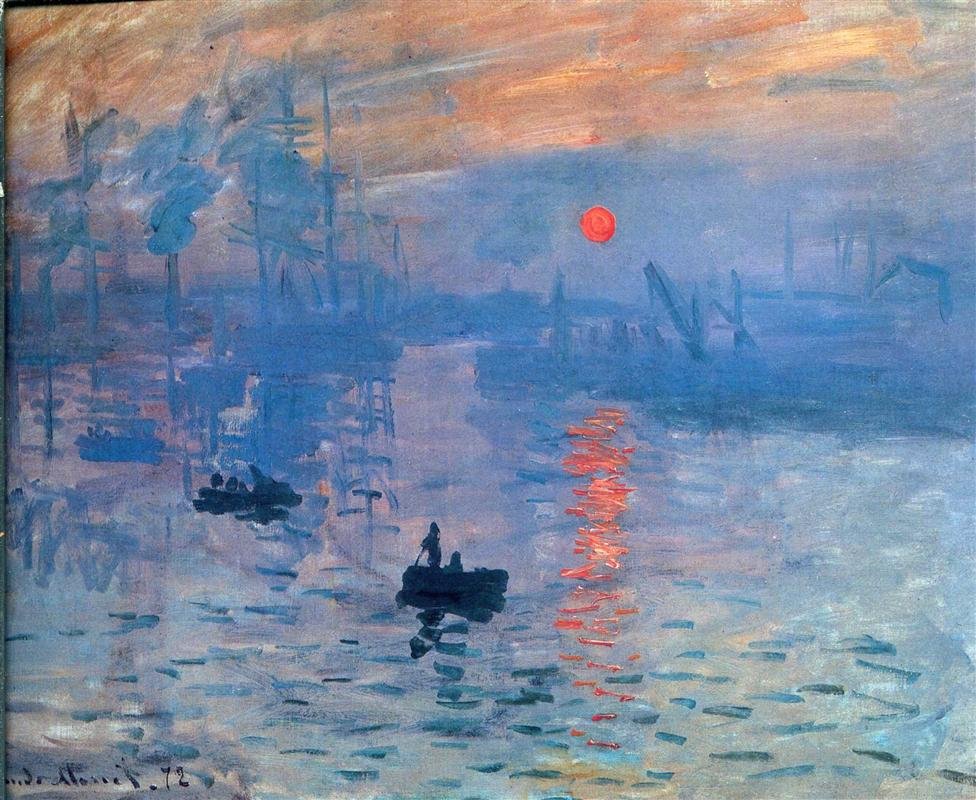

Painting en plein air is inseparable from the rise of impressionism, so it’s worth discussing here. One could say that all formal impressionism starts en plein air but not all plein air work is impressionistic. European outdoor painting was pioneered by the Barbizon School and I Macchiaioli, which directly influenced early impressionists. In North America, however, painting outdoors was born largely from the western expansion with the Hudson River School active as early as 1830. Impressionism on both sides of the ocean is most easily identifiable by its loose abstraction of broken color, which again further reflects the movement away from the rigid structures and barriers around the creation of art. In the west, the impressionists took some of the first steps away from stark realism as the mode and ironically went to paint the real natural world free from the “perfection” enforced on it by humankind to redefine ideal beauty.

Advances in art materials may have made it possible for artists to effectively work in the field, but it was a shifting mindset that made people want to work outdoors. It’s a common thread to ask what defines art and what drives humans to create. It’s maybe impossible to create a lasting characterization because people seem always to be driven to what’s new and changing, yet old and familiar. What, then, could meet those requirements better than the natural world around us?

(1) For much longer, you’d only see natural landscapes as a backdrop for a subject and rarely the subject itself. Even then, although sketches of local physical features may have been done as reference, finished works would rarely feature a true representation of actual landscapes

(2) This is a thing I regularly, and understandably, hear angst from especially in the community of actually-starving young artists: Rich people used to PAY artists a living stipend to make art. Unfortunately, this did come with a lot of strings attached in reality. Do we really want to paint another portrait of our Medici sugar-daddy in the exact same style as the last thirty? Do we really want to paint another depiction of the same religious scene for the pope that’s been done and done again for centuries? Idk. We take the good with the bad.

(3) A famously fun, groovy, and forward-thinking organization.

(4) And if there’s anything creative types hate, it’s being told what they can and cannot do.

(5) Because, again, my special interest at its heart is the art materials lol. Other people can definitely tell you more about the technique and even about the cultural ramifications of changes brought on by the introduction and adoption of plein air painting as a valuable technique. For me, the interesting thing is always going to be how a new artistic doodad facilitated those changes. In this case, the big player was paint tubes. They allowed for two very big changes in that artists no longer were exclusively responsible to mix their own paint from raw pigment and that they then had an easy way to transport and preserve that paint beyond their indoor workspace. This opened the door for art suppliers to operate and for artists to create with greater flexibility.

(6) This is something I’m realizing I have big thoughts and feelings about that I don’t want to sacrifice word count for in the main body of the post. A major aspect of the classical mindset that we see in everything from visual art to architecture and cultural beliefs is that nature is only good and beautiful if carefully tamed by humanity. Rigid, but compelling, proportions. Perfection. The elimination of mystery and fear and danger from the wild was a reflection of the very real dangers faced by Europeans in the late middle ages as well as those posed to early colonial efforts by organized heathen societies. The slow distancing of this mindset by the artistic community was mirrored by the rebellion of artists from the confines of traditional structures of how art should be taught, how it should be created, and what it should be about. This period of the latter 1800’s saw a rise in interest and appreciation for the natural beauty of the land as well as the normal people who lived there. This updated mindset regarding the inherent balance of raw nature was represented in everything from art and gardening practices to the Origin of Species.

(7) A very cool sounding term that effectively means that the colors are left unmixed on the canvas. Does this make comic books impressionist art? Discuss.

(8) Damn, I definitely said this was going to be focused on art materials but the word count completely got eaten up talking around the inherent beauty of change. Oh well, I reckon that might resonate with more people on a soul level than talking about how cool metal tubes of paint are if you really think about it.

(9) Check out my blog post on Tolkein and Bob Ross because I *really* like thinking about why on earth people feel compelled to create and so few other species seem to have any kind of similar drive to the degree we do. I’m not a big fan of the concept that creativity is some kind of divine gift, but it’s hard not to look at humans with some degree of exceptionalism and awe at the things we have created, are making now, and have yet to conceive.

(10) Probably something, it’s not a riddle with one specific answer, but that’s kinda the point isn’t it?