What Does art do for us? What’s the point of it all?

And what does an art school that only existed for Fourteen years have to do with it?

Have you ever found yourself at a museum of contemporary art wondering “why is this art good?” or more accurately “why have so many different people all decided this art is good?” You may not even have to be in a museum to experience this symptom. We live in a world, thankfully, surrounded by art for better and for worse. The buildings we walk by, the cups we drink from, and the advertisements we skip past aren’t always good art, but what if they were? Or worse yet, what if they were all weren’t?

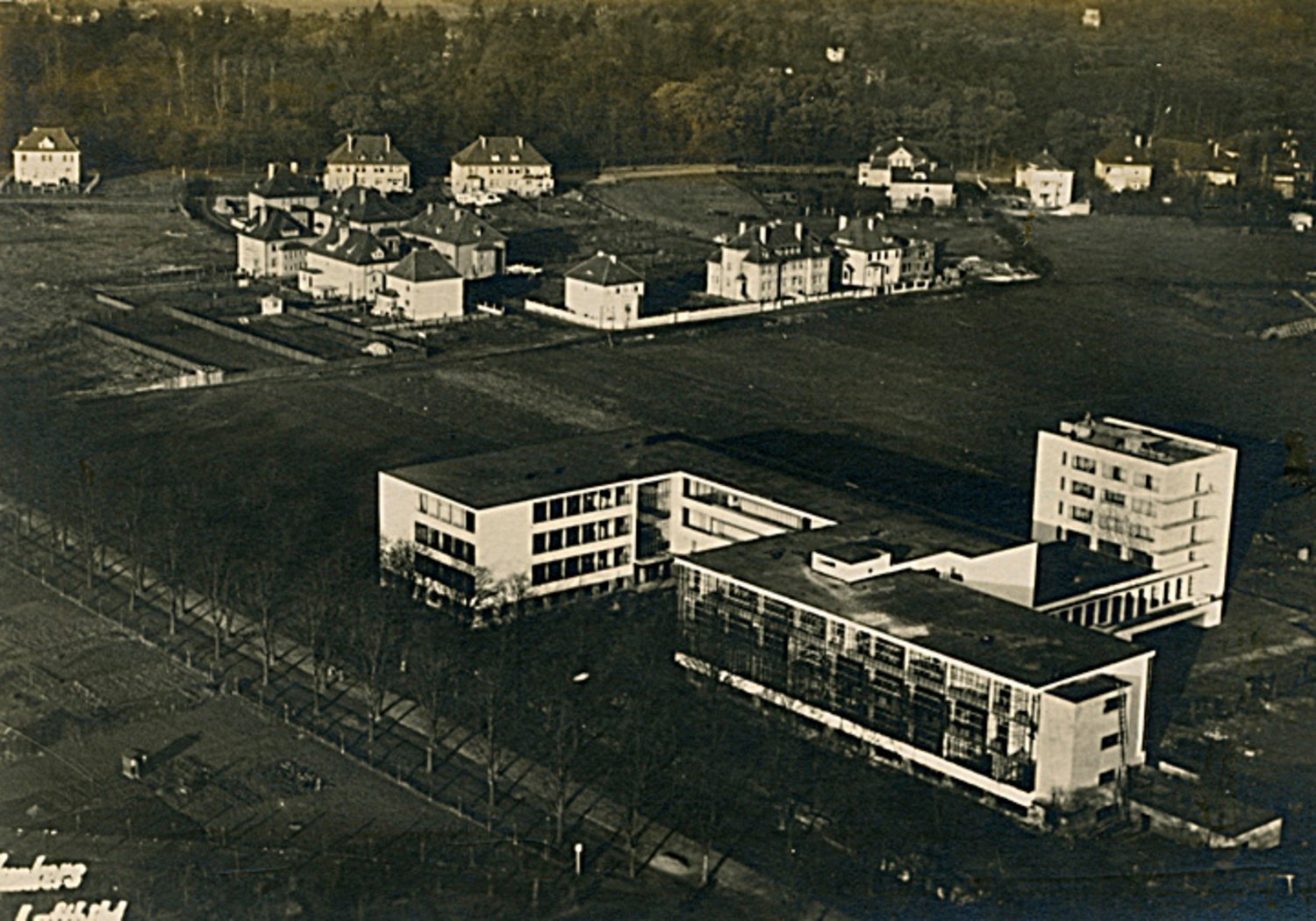

Something special happened in Germany in 1919. Life was changing for many, and many had never returned from a war that was promised to last no longer than two years and be the war to end all wars. In the midst of this reshuffle, an architect from Berlin was recommended to restart and head a combination of two premiere German art schools that had languished during wartime. Walter Gropius established the Bauhaus school, and within a few short months this school began educating razor sharp artists and craftspeople like a machine.

Bauhaus doesn’t really have a mega-perfect English translation, but loosely it means “House of Architecture.” Bauen: to build. Haus: House

The school’s founding manifesto pulled no punches and is steeped in analogies between the crafts and a literal spiritual awakening(1).

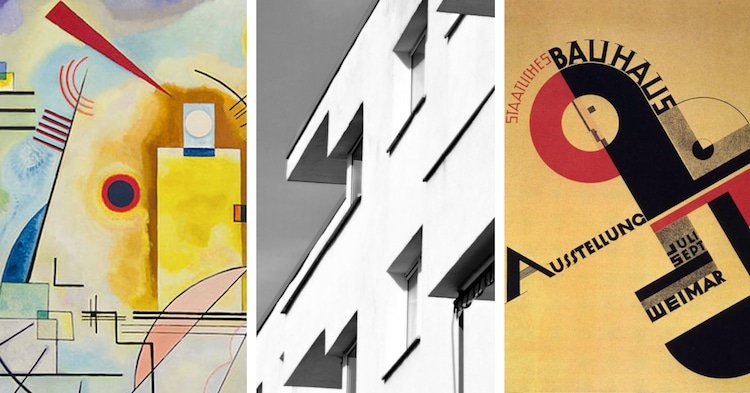

Throughout his tenure, Gropius promoted the Gesamtkunstwerk (ge-samt-KUNST-werk), or comprehensive artwork(2). This divergence of more traditional aesthetic philosophy may be interpreted almost as a criticism of creativity, but in practice it prompted creative people not to view the only path available as an artist to be cloistered in a studio. In addition to a foundational education in the fine arts, the school taught courses in everything from cabinetry to costuming, textiles to typography, and ceramics to carpentry. Its aim was to elevate the design and craft of the world we create around us and reduce the gap of class between craftspeople and artists. At Bauhaus, art was design and design was art.

As with many things of the period, this experiment in creativity was diminished and then destroyed entirely by the destabilizing rise of far-right politics(3). In 1933, after relocating several times, the school was forced to close. Artists, whether staff or students, were compelled to either conform to the new regime or emigrate. Lucky for us now, many chose the latter option. The design concepts of the Bauhaus were welcomed internationally, took root, and continued to blossom.

The artists of the Bauhaus never quite managed to attain their ideal of the comprehensive artwork. This radical idea did, however, succeed in combining the creativity of artists with the practical applications of craftspeople(4). With a focus on creating for mass production and communication, this way of thinking had set everything up for us to enjoy the many beautiful aspects(5) of the relatively beautiful world in which we live today.

Think what you will about the current mass production of consumer goods(6), but communities today would have a difficult time maintaining current expectations of comfort solely by the cottage industry that met these needs before. In this previous era, the craftsperson could create artisan work for everything from a bowl to a building. To meet those needs today, we rely on the mass manufacturing that the Bauhaus planned for a century ago.

There’s a lot to like and dislike about the modern movement of art that peaked throughout the 20th century(7). Regardless of opinion, these ideas do create a through-line to the ubiquity of design around us today. Regardless of what we may like as individuals, we can count ourselves lucky for the efforts of the artists around us(8).

(1) “Architects, sculptors, painters, we must all return to the crafts! For art is not a “profession.” There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an exalted craftsman. In rare moments of inspiration, transcending the consciousness of his will, the grace of heaven may cause his work to blossom into art. But proficiency in a craft is essential to every artist. Therein lies the prime source of creative imagination.” -Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Manifesto (1919)

(2) I had a professor in college who taught scenic design for the stage as well as general design communication. It’s safe to say he was obsessed with the Bauhaus school and probably just wanted to teach architecture specifically because that’s what he usually did anyways. Despite initially feeling like he was a crazy person, I eventually really began to understand where he was coming from, and now here I am writing an incredibly condensed soapbox piece on why the Bauhaus is the best and saved the 20th century from mundanity. I think that studying Bauhaus design and philosophy was particularly helpful in academic theater, since a work of theater succeeds or fails by the collective efforts of every designer, actor, and the director trying to keep everyone on the same page. Although generally no single person oversees all these disparate aspects, the end product is a comprehensive artwork meant to be seen as a single piece.

(3) The Nazis were super into art and design as long as it, and everything and everyone else, never disagreed with them and made them look super cool and smart. A tall order.

(4) Art was, and still is in many regards, a practice reserved for the higher classes. As a huge generalization, typical people have had to work at other tasks to generate enough wealth to feed themselves and their families. On the one hand, we saw artists like Van Gogh and Vermeer who constantly sat at the edge of destitution during their careers, yet since about the 1600s the work of creating art had shifted from accomplishing a physical task to an intellectual one. This is all on top of the shift in humanist philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries away from justification of ‘nobility by birth’ to ‘nobility by character and culture.’ I think the Bauhaus ideal of bringing art and craftsmanship together again is quite a beautiful conclusion to that arc at the start of the 20th century.

(5) I feel like I keep managing to talk around this point in the main body without ever really hitting it right on the head, so here it is: We are so lucky to live in a world with artists, and everything that threatens to devalue the arts also risks such an egregious cascading effect. If you follow the thought through to its conclusion of what a world without art would be like, it’s pretty horrible. There would be no need for color, we would all be either dressed the same or for whatever specialized task we were expected to do. There would be no need for advertisements as there may be only one tool available to accomplish a task. No television. No music. It all sounds incredibly silly, like the Vogons from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, because there’s something in us deeply attuned to aesthetics. I don’t think we’ll ever really achieve this nightmare situation, but I’m always disappointed when the job of a creative is replaced by something else or when the most resources go to projects simply meant to achieve the best return for investors rather than contribute to culture in a meaningful way. The focus of art in design that spread from interwar Germany may have done a lot towards saving us from a blander world today, but artists need to be allowed to continue doing our part!

(6) If you wanted MY two cents, I’d love to see consumer goods able to be used for a longer period of time. Things made by dedicated craftspeople generally last SO much longer, but paying them a fair rate is incredibly prohibitive for many consumers. I just spent the weekend with some people in the 1%, but for me, there’s unfortunately no choice to be had between a mass manufactured bed frame that will break in five years versus a handmade one that would last a lifetime. This is kinda like that argument about a poor person having to spend more on many pairs of cheap boots compared to a rich person spending less on a single pair of more expensive boots. Products, clothes, computers, and everything else designed to be obsolete or in tatters in a matter of months or years is bad for the people at the end of the supply chain as well as for the planet.

(7) Speaking from personal experience. We can each have our own personal interests that inform what we like and don’t like. I have a hard time getting anything from uninspired prints thrown together en masse and available at big box stores, but it’s rare that I’ll be in a museum or gallery room and see absolutely nothing worth seeing. Even if it’s just an aspect or two of someone’s work.

(8) If you’re an artist reading this, thank you for whatever it is that you do. If you’re an underappreciated artist, doubly so. If you're not an artist, SURPRISE you actually are. I don’t make the rules ¯\_(ツ)_/¯